A federal judge in the lawsuit brought by dancehall producers Steely & Clevie ascertaining their copyrights over the 1989 Fish Market Riddim has raised concerns over the nature of the suit.

The lawsuit names hundreds of artists, including Karol G, Pitbull, Anitta, Drake, Daddy Yankee, and many others, for their sampling of the Fish Market Riddim to create reggaeton music.

Clevie has long been recognized by his Jamaican counterparts as the creator of the dancehall genre, and his Fish Market riddim spawning the birth of what is now called in the Latin music world as Reggaeton and Dembow.

However, the lawsuit implies that Steelie & Clevie may own the genre, and this may stifle “creativity,” a concern raised by the Judge in the lawsuit.

On Friday, lawyers for the plaintiffs and the defendants appeared in court for a hearing to dismiss the case brought by attorneys for Bad Bunny. U.S. District Judge Andre Birotte Jr. presiding has not issued a ruling as to whether Bad Bunny’s motion to dismiss will be granted.

During arguments, the plaintiffs said that the Jamaican producers’ lawsuit concerns their 1989 hit “Fish Market,” which was sampled and created the distinctive Dembow riddim, which is what many now know as reggaeton.

However, the Judge questioned whether the defense’s arguments that allowing the lawsuit to proceed or allowing it to be successful would “monopolize” the reggaeton genre.

The lawsuit brought by Clevie and the estate of Steely says 1,800 songs by 160 defendants used the Fish Market riddim. They were not authorized or compensated the producers for the use of the track.

The Judge specifically raised the notion that Jamaican music has influenced other genres, but that may not be the case.

“What’s the end game? Does this lawsuit run the risk of arguably stifling creativity?… Look at the ripple effect this style has had on reggae, reggaeton, Latin music, Hip-Hop, you name it. Does this stifle the creativity of all of those genres?” the Judge questioned.

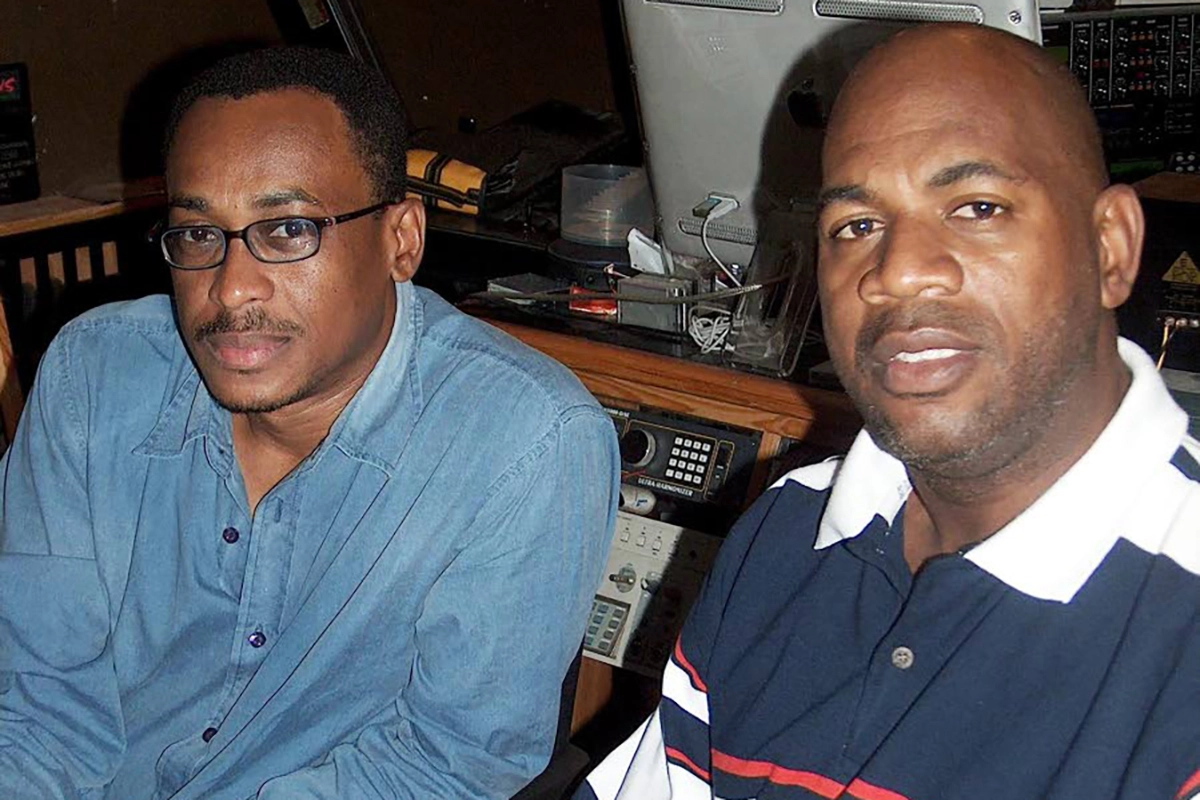

Scott Burroughs, the lead attorney for Clevie, whose real name is Cleveland Browne, and Steely, whose name is Wycliffe Johnson, however, says that it might be time for a “reckoning” to reign in artists who wantonly breached protected works of others who ordinarily would not pursue the matter because they lacked knowledge, power or wherewithal to pursue them.

According to the lawyer, the defendants respect and operate above board to clear samples of other artists and even themselves when others use their music, and to dismiss the lawsuit means that his clients would be “left out in the cold.”

Kenneth D. Freundlich, the lawyer for Bad Bunny, denied that his artiste infringed on the Fish Market riddim copyright in more than three dozen songs named in the suit. According to him, his client did not sample the Fish Market riddim.

Furthermore, he raised the point that the lawsuit centers on Bad Bunny’s composition use of certain elements, but his client used different instruments, synthesized sounds, and timbre while only the drum riddim remained. He argued that the drum riddim is not protectable.

However, the attorney asked the Judge to throw out the written composition infringement claims.

“I want this to be cut down by 75%, with the musical composition out of here. And frankly, I don’t think they’re going to have any claims against Bad Bunny left, because there’s not a sample in there,” the lawyer argued.

Arguments were also raised as to whether a “Fish Market” drum riddim is protectable under copyright law, and that would depend on whether it was original and taken or sampled from someone else.

A question was also raised as to why the producers registered “Fish Market” in 2020 only and why no lawsuit was brought against an earlier sampling by Denis Halliburton in the 90s hit “Pounder Riddim,” which used Fish Market’s drum riddim.

“An entire genre of music, reggaeton, grew up over 30 years. Did they sue? Did they bring a claim? Did they do anything? No,” Donald Zakarin, representing Luis Fonsi and others, said.

Zakarin also claims that the producers were not the owners of the Fish Market riddim, something rebuffed by the claimant’s lawyer Burroughs during questions about whether there was ‘Prior Art’ before Fish Market.

“One way you look at that is, ‘What existed?’ Well, there was revival music… they heard this in the streets of Jamaica. They heard these beats, they borrowed them. So what? They borrowed this piece, that piece. That means it’s not new or novel,” he said.

Burroughs, however, said there was “prior art” to be considered since, until Fish Market, no such work existed.

“In 1989, when this song was released… this was an original work, there was nothing like it,” he said, adding that the song featured seven discreet elements.

“So your view is that before this, nothing like it existed? The boom-bap-boom-bap sort of rhythm, you think there was nothing like it before it?” the Judge questioned.

“How would you distinguish this, if at all, from the traditional dancehall rhythms used since I was a kid in reggae? If you go on the streets of Jamaica… big speakers, same beat,” Birotte said, adding he was a college DJ and owned CDs of similar riddims.

The Judge did, however, argue that there were triable issues raised by both sides but did not offer an immediate ruling.