Jamaicans are reveling at the latest announcement that footwear brands Adidas and Clarks have put out statement shoes in homage to Jamaican people and culture. Crisp new shoes featuring iconic Jamaican colors- black, green, and gold, which are the colors of the Jamaican flag adorn the shoes along with the name ‘Jamaica’ even though the shoes have no connection to or have been made in Jamaica or by Jamaicans.

Adidas announced the March 26 release for the Originals by Wales Bonner for the company’s Spring/ Summer 2021 collection and says it is the second collaborative collection which is inspired by the 80s origination of dancehall music in Jamaica. The first collection of shoes called “Lovers Rock,” released in Autumn/winter 2020, reflected on the British-Jamaican diaspora in London in the Seventies.

In a commercial to mark the arrival of the new shoes, a group of Jamaican jockeys dressed from head to toe in Adidas attire feature with their horses. The video starts with the jockeys waking in the morning to the tunes of reggae music playing as they go about their daily activities. The company says the collaboration builds on “Wales Bonner’s exploration of the diasporic connections between Britain and the Caribbean.”

The video announcing the new collection shows Jamaicans playing football and others tending to their horses or riding. The only reference to music is the track underlying the advertisement – a sample of Cornell Campbell’s A Poor Jah Jah Man from his “The Gorgon” album released in 1976.

“Adidas Originals and Wales Bonner (designer) return for SS21 with Essence – an exploration of the connection between Britain and the Caribbean. With a focus on tailoring, the capsule sees rich Jamaican references stitched into iconic adidas looks,” the company said.

“Wales Bonner and Adidas Originals have another collaborative collection on the way, which traverses the early 1980s era of Reggae when Dancehall music became a staple in Jamaica”.

Adidas joins other companies like Clarks, who also made a recent announcement of shoes that supposedly pay homage to Jamaica using the country’s rich music culture and unique effect on the world- to sell their shoes.

Clarks has been a beloved of Jamaicans, first being the shoes of choice for Rastafarians. They resurged to popularity in Vybz Kartel’s popular “Clarks,” which echoed the country’s love. Even the Jamaican Prime Minister Andrew Holness’s apparent love for the shoes has caused a resurgence of the Clarks trend as he matches his shirts with his favorite shoes.

According to Clarks, the company will be releasing a range of beloved styles in April, and they plan to use some Reggae and Dancehall artistes as brand ambassadors to promote the collection. However, while the companies might have the admiration of shoe fans, local cultural experts are sounding the alarm that while foreign companies rake in big profits- the people who keep the culture alive have to eke out a living and should be compensated for being the source of inspiration for their products.

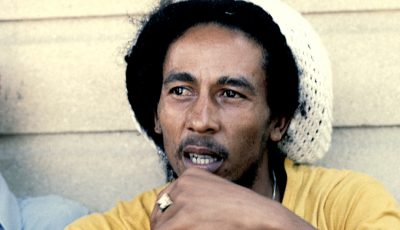

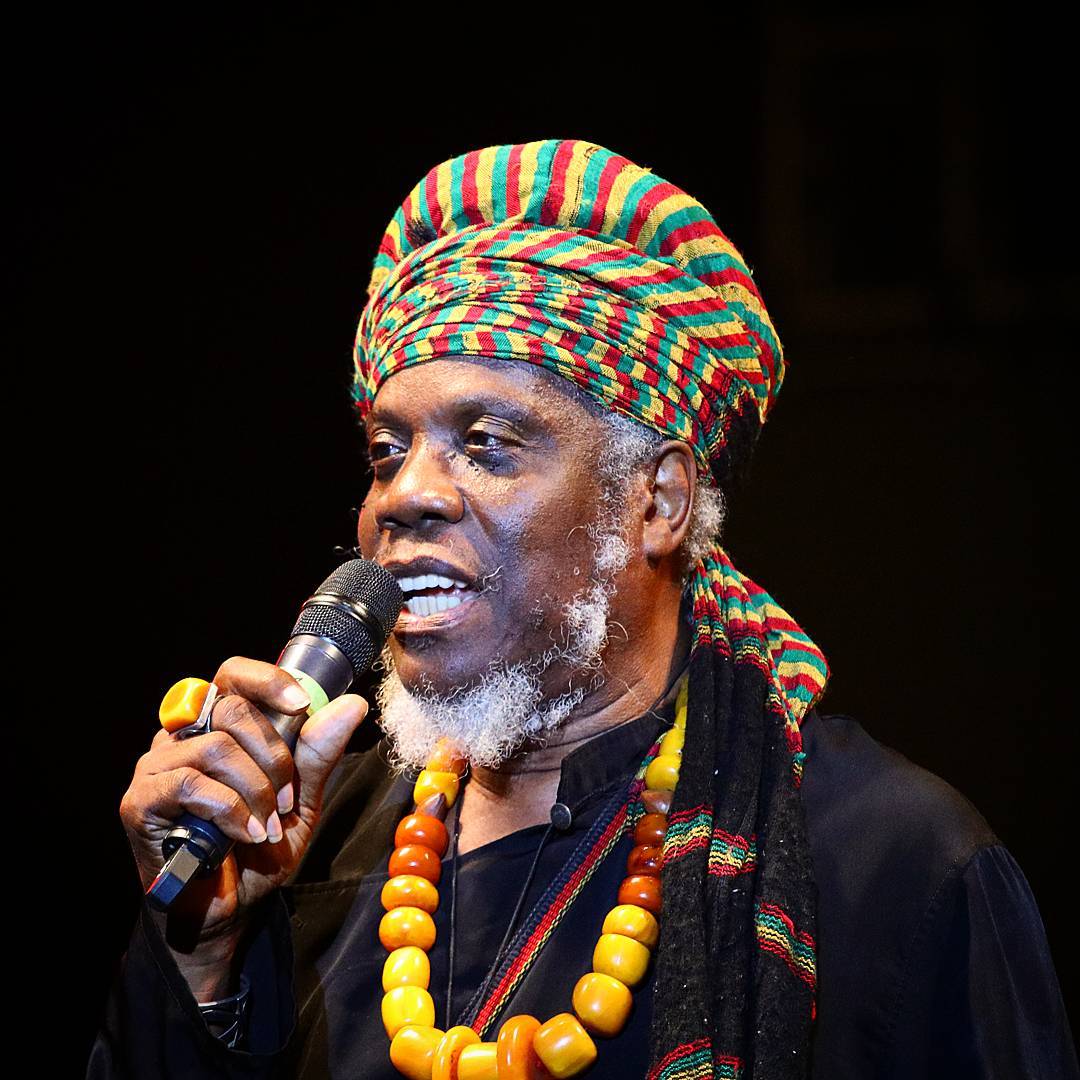

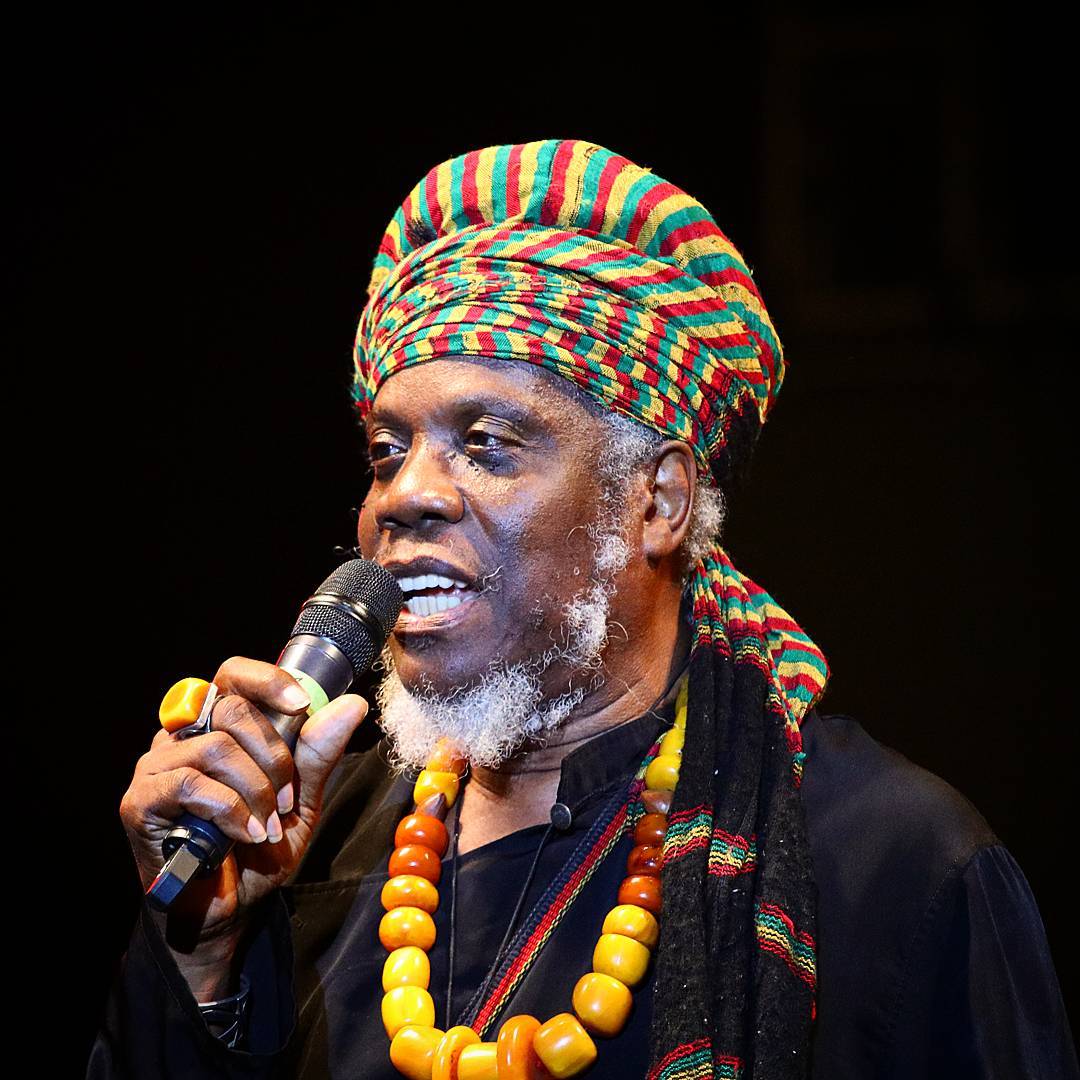

Among those who have criticized the companies for blatantly expropriating Jamaican culture are Dub Poet and Afo-historian Mutabaruka. He not only criticized the Prime Minister for wearing his iconic Green Clarks Deserts boots – the color of his political party, but also for choosing to indirectly promote a foreign brand. However, there are few noteworthy shoemakers locally.

He also rubbished the company’s plans to use dancehall artistes calling it a “terrible thing” for the island. “the promotion of the Clarks by the Dancehall artistes…mean say dem wi get pay like if dem ah do a show…but the selling of the Clarks will continually be sold under the guise of ‘here’s some Jamaican dancehall youth ah wear dancehall bootie’ out there…”

Professor Donna P. Hope, who heads the Institute of Caribbean Studies and the Reggae Studies Unit at the University of the West Indies, says the time has come for Jamaicans to be compensated somehow when they or the culture is used.

“What is happening today 2021 isn’t something new. One of the challenges we are having is these individuals, these companies from outside of Jamaica, who have been and I would say have been allowed and given opportunities to come to Jamaica and use Jamaica or Jamaica’s cultural artifacts to either market their products or create new products and reap profits for their shareholders and family members… what would be different in this era to make them want to turn around and repatriate either profit or some benefit back to the people of Jamaica?, is a question we must ask,” she said.

She says what the shoe brands are doing is akin to saying that because Jamaicans love the Clarks and Adidas brands, the companies by paying homage to use the Jamaican culture to promote their shoes- are giving Jamaicans something but, in reality, Jamaica is a much bigger and influential brand that companies by using the brand benefit far greater and for longer extensive times.

She referenced the island’s dominance when it comes to music – having been one of the inspirations of many new genres of music as well as the island’s reputation as an athletic powerhouse but more so- the natural flamboyance of the Jamaican people that has seen the likes of the greatest celebrities and artists coming to the island to use its people and resources as sources of inspiration.

The issue of Trademarking Jamaican culture

While it might be difficult to now attempt to trademark aspects of the Jamaican culture, Dr. Hope believes that the conscionable thing would be to give back to the island tangibly. “perhaps they should give a scholarship or two for children from Jamaica’s working class, Kingston’s inner cities that they can go do a court in fashion at Edna Manley or something.”

Dr. Hope believes that from a national level, the government needs to have a sit down with Adidas because while the footwear is from outside, it has become rooted in Jamaican culture.

“We have had these conversations in culture and in the music with fashion from outside of Jamaica because we haven’t had a very indigenous fashion culture that people could really identify any real brands but we have adapted these outside brands which became big in Jamaican popular culture,” she said.

“What people are doing out here is going and pay homage to these brands based on our popular culture. What we are doing is marketing these brands for them. I looked at the ad which they say they are paying homage to dancehall, there are no messages that resonate with dancehall, the sounds, the fashion, the people in it, so nothing in identifiable with dancehall from a Jamaican/Caribbean perspective, there are black people there yes, but the setting it wasn’t a stage show, nothing that resonates with dancehall,” the Dancehall expert said.

According to Dr. Hope, the company and others like it, including the artists in other countries, ought to provide reparations for being allowed to come to use our locations, people, sounds, and ideas to market their products. She cited the proliferation of artists and celebrities visiting the island and creating dancehall collaboration as well as the number of them who are declaring their Jamaican heritage, which previously was not known.

Meanwhile, Dr. Hope notes that with dancehall becoming known worldwide, the recent Verzuz with Beenie Man and Bounty Killer shows that the genre is getting a lot more attention. She, however, notes that with the advent of social media driving the spread of the culture- there is a risk that Jamaicans will lose their culture unless something is done to protect it.

“Wat’s unique about dancehall is that people who are seeing it and hearing it not only want to buy the products but they want to be the products because of the potential for returns so that they too can be a superstar and have status and be a celebrity, be an influencer and there is a lot of that going on that others see value in.”

She added that while more foreigners are becoming interested in the culture and making money from it, citing the evolution of dancehall dancing becoming popular in Europe and genres like Afrobeat and others cropping up, Jamaicans locally still view dancehall as negative and bad.

“We’re seeing a lot of ways as negative and bad and we’re not marking the movements of dancehall culture. Some of us are doing some work but others are occupied with the negative…and that’s the end of the conversation.”

She added that the mindset has to change locally because dancehall is impressive to outsiders, as many who are not even English speakers gravitate to Jamaica and the genre.

“It’s breaking across many borders and the levels and layers that are coming out because one of the challenges we have in Jamaica is that because of our level of creation of music and sound and the proliferation of people that we are producing that gets into the music and quickly rises up, we take it for granted but when you are on the outside looking in people are impressed, they are amazed and they want a piece of the action,” she said.

She warned that until Jamaicans take a step in becoming involved as well as taking control of licensing and monetizing aspects of their own culture, the next ten years will see scholars in the genre that are not indigenous, and that will be a problem as non-Jamaicans tell the story of Jamaicans. More so, until Jamaicans can demand their worth for use of their music, culture, and other iconic Jamaican things, there will be no financial benefit to them even as foreign companies and figures continue to exploit the mystique of the island.